While the benchmarks I recently posted showed a lot of promise for combining MessagePack C# with CoreRT, I wanted to run it with a real world example to confirm that this is worth the effort, so this evening I updated Last 'n Furious, now available on itch.io.

The original version was 97MB, which zipped down to 41MB. The second iteration - using ReadyToRun, PublishTrimmed and Warp as detailed here - came to 32MB. The new CoreRT version is 45MB which zips down to just 16MB, so we have halved the size.

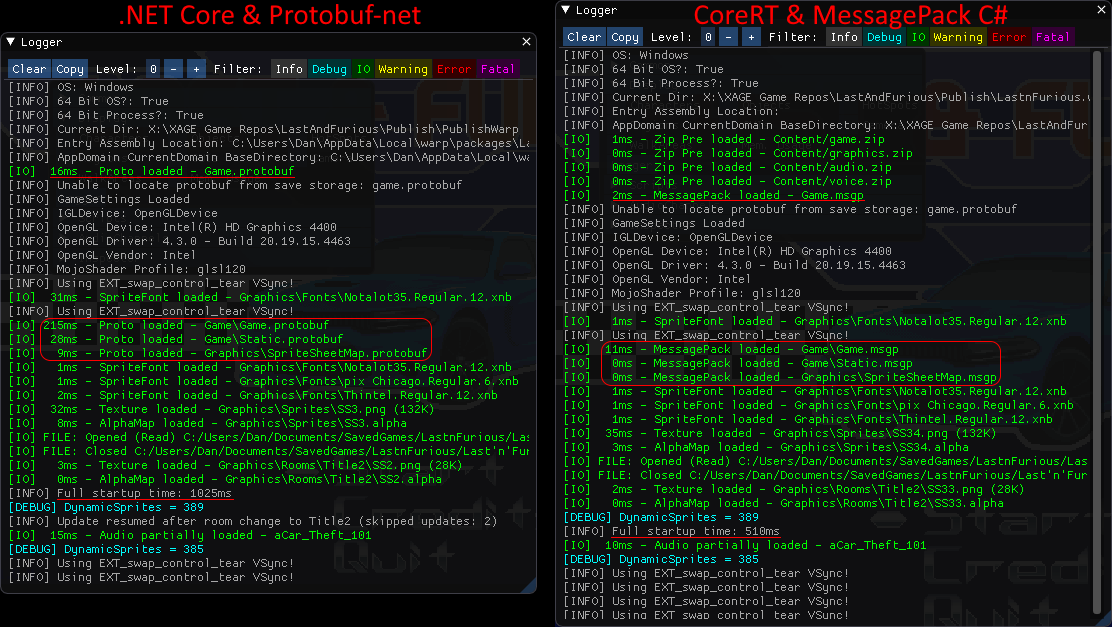

Where previously I'd been happy to get in-game in about a second, the CoreRT version now shows the main menu screen in half that time. It feels snappy like a native executable. The improvements can be clearly seen side-by-side:

As always, there's more work to be done to integrate MessagePack fully into XAGE's pipeline, but the results already justify the effort involved.

Tuesday, 10 March 2020

Saturday, 7 March 2020

Experimenting with MessagePack

Serialization keeps me up at night.

For many genres, saving the game state may be as simple as recording what the current level is, along with a score. For others, like RPGs and Adventure Games, things get a lot more complicated when you're having to save the state of every item in the game at any given point.

There are many serialization mechanisms available to choose from. For XAGE, the needs are:

Early versions of XAGE used XML for the game state (and still do within the editor tools, as it is version-control friendly) but evolved to use Protobuf-net, a C# library that allows you to perform contractless serialization in Google's binary format. This improved performance and file size significantly, but had one major drawback - lack of AOT support, required by some platforms like iOS and UWP.

Protobuf-net initially had AOT support by pre-generating a serialisation library, but official support for this was dropped. The author has been waiting for Roslyn Generators in order to embed the serialization algorithms in at compile time. Unfortunately this has not yet materialised and remains on the future roadmap.

Other serialization libraries exist with AOT support like Ceras, but without version tolerence, so have not been considered.

One I've had my eye on for a while is MessagePack for C#, which has long promised fast serialization times and low payload sizes with LZ4 compression. Recently their AOT solution - a seperate executable called mpc.exe to generate the serialization logic as C# code - has become available as an MSBuild task, essentially allowing you to automate this process.

MessagePack's benchmarks always looked promising, but it's always important to test using your own data structure - in my case XAGE's main GameContent class. For this I used BenchmarkDotNet which has become the industry standard for getting consistent and meaningful .NET benchmarks. With this I was able to get results comparing the standard XML Serializer, Protobuf-net and various flavours of MessagePack (all using string keys rather than integer keys, for version tolerence):

However it wasn't all plain sailing as:

Here the benefit of pre-generating the serialization logic is clear to see (MPC), but the performance of the CoreRT incarnations blew the rest away. What took XMLSerializer 1247ms and Protobuf 848ms took MessagePack just 36ms from cold. Adding LZ4 compression to reduce the filesize to 255K only brought this up to 40ms. I dumped the GameContent as JSON in the benchmark cleanup methods to confirm the data was actually being loaded and saved correctly, as I didn't believe the results at first.

While it would take some time to fully integrate MessagePack into XAGE, it currently appears to be the best option in the absence of protobuf AOT support. I just hope that .NET 5's AOT strategy works as well as CoreRT.

For many genres, saving the game state may be as simple as recording what the current level is, along with a score. For others, like RPGs and Adventure Games, things get a lot more complicated when you're having to save the state of every item in the game at any given point.

There are many serialization mechanisms available to choose from. For XAGE, the needs are:

- Performance - the faster the better.

- File size - too large a payload can typically affect performance, especially when disk IO is a bottleneck.

- Ease of use - from both an engine and game perspective, the user should be free to think about serialization as little as possible. So no contracts or schemas, ideally no per-field attributes, and built-in version tolerence.

- Platform support - must work on all platform, including those with restrictions on JIT.

Early versions of XAGE used XML for the game state (and still do within the editor tools, as it is version-control friendly) but evolved to use Protobuf-net, a C# library that allows you to perform contractless serialization in Google's binary format. This improved performance and file size significantly, but had one major drawback - lack of AOT support, required by some platforms like iOS and UWP.

Protobuf-net initially had AOT support by pre-generating a serialisation library, but official support for this was dropped. The author has been waiting for Roslyn Generators in order to embed the serialization algorithms in at compile time. Unfortunately this has not yet materialised and remains on the future roadmap.

Other serialization libraries exist with AOT support like Ceras, but without version tolerence, so have not been considered.

One I've had my eye on for a while is MessagePack for C#, which has long promised fast serialization times and low payload sizes with LZ4 compression. Recently their AOT solution - a seperate executable called mpc.exe to generate the serialization logic as C# code - has become available as an MSBuild task, essentially allowing you to automate this process.

MessagePack's benchmarks always looked promising, but it's always important to test using your own data structure - in my case XAGE's main GameContent class. For this I used BenchmarkDotNet which has become the industry standard for getting consistent and meaningful .NET benchmarks. With this I was able to get results comparing the standard XML Serializer, Protobuf-net and various flavours of MessagePack (all using string keys rather than integer keys, for version tolerence):

- LZ4: Where the payload is compressed using this performant compression library.

- MPC: Where the serialization logic is generated by mpc.exe at build time, rather than determined and emitted at runtime.

- CoreRT: Using the CoreRT AOT runtime, instead of .NET Core 3.1 (where use of mpc.exe is required)

However it wasn't all plain sailing as:

- I couldn't use the BenchmarkDotNet nuget package as the latest SimpleJob overloads weren't in place, allowing you to combine a ColdStart test with the CoreRT runtime.

- I couldn't use the MessagePack nuget package for the CoreRT tests due to some emit issues that are outstanding. Compiling from scratch using some conditional symbols (NET_STANDARD_2_0; UNITY_2018_3_OR_NEWER; ENABLE_IL2CPP) resolved this.

- All my classes had to be decorated with MessagePack attributes, and all public properties not needed with [IgnoreMember].

- Protobuf-net's surrogate mechanism (for types like XNA's Vector2 and Color classes) is not supported and had to be reworked to be more generic in order to support MessagePack.

Once these issues were resolved, I was able to test with the largest GameContent data I had, and the results were surprising:

Note that these are 'Cold Start' benchmarks - i.e. single iteration tests with no warmup, repeated many times over.

Here the benefit of pre-generating the serialization logic is clear to see (MPC), but the performance of the CoreRT incarnations blew the rest away. What took XMLSerializer 1247ms and Protobuf 848ms took MessagePack just 36ms from cold. Adding LZ4 compression to reduce the filesize to 255K only brought this up to 40ms. I dumped the GameContent as JSON in the benchmark cleanup methods to confirm the data was actually being loaded and saved correctly, as I didn't believe the results at first.

While it would take some time to fully integrate MessagePack into XAGE, it currently appears to be the best option in the absence of protobuf AOT support. I just hope that .NET 5's AOT strategy works as well as CoreRT.

Tuesday, 5 November 2019

Putting lipstick on Sisyphus

Development has been somewhat chaotic lately. Instead of focusing on one or two particular areas, I've been hammering away at my TODO list - all the little bugs and enhancements and quality-of-life improvements needed to get XAGE in a shippable state. I'm regularly pushing out new builds of the tools to itch.io to get into good habits as part of an established release process.

Having said that, a number of recent changes have a common theme, which is either to reduce the CPU usage (particularly startup time) or reduce the disk/memory requirements. Often these optimisations work against each other, so it has taken some experimentation to determine which combinations achieve the best balance.

I've released an updated version of Last 'n Furious with the above improvements. The result is a single executable that is smaller (32MB) than the previous version (40MB zipped). After the initial run, the game starts up in about 1 second, which is about as good as it gets until we are AOT-compiling the final executable in .NET 5.

CPU usage is down slightly, hovering around 2-3% CPU mid-race on my old laptop compared to 4-5% on the previous version. Memory usage is also down to about 180MB compared to 220MB before.

Mac and Linux builds of the game also exist, though are not yet available due to an outstanding texture issue that only seems to affect the Mac platform - this should be resolved once I get my hands on some actual Apple hardware, like one of the ten richest kings in Europe.

Getting there.

Having said that, a number of recent changes have a common theme, which is either to reduce the CPU usage (particularly startup time) or reduce the disk/memory requirements. Often these optimisations work against each other, so it has taken some experimentation to determine which combinations achieve the best balance.

- The custom BitArray ("BooleanMatrix", for fast alpha detection on textures) was changed to use a RoaringBitset implementation. This massively reduces the amount of storage space needed, both file and memory, at a slight performance cost at runtime.

- The pipeline was changed so that the PNG spritesheets are published as LZ4 compressed 32-bit bitmaps. While testing with Cart Life I'd noticed some frame drops while loading in a 4K spritesheet mid-game. The LZ4 compression has an extremely fast decompression rate, and having the raw bitmap data removes the need to decode from the original PNG in-engine. This loads in textures much more quickly at a cost of moderately increased file sizes.

- Profiling indicated that FAudio, the audio engine used by FNA, was slow to initialise. By warming this up on program entry on a throwaway thread, we're able to shave a second or so from the initial startup time.

- The GameSettings file is now stored as protobuf file, removing a minor XML deserialization performance overhead (a few 100ms).

- Using the 'PublishTrimmed' option on the game project has the linker remove unused code, which reduces the final package size.

- Using the 'PublishReadyToRun' option - a sort of mini AOT solution - reduces the start up time, at the cost of increasing the final package size.

- Warp was used to produce the final package (as the 'PublishSingleFile' option is not mature enough yet). Packaging it up in this way increases the very first start up time but reduces the final package size and makes it easier to distribute and run.

I've released an updated version of Last 'n Furious with the above improvements. The result is a single executable that is smaller (32MB) than the previous version (40MB zipped). After the initial run, the game starts up in about 1 second, which is about as good as it gets until we are AOT-compiling the final executable in .NET 5.

CPU usage is down slightly, hovering around 2-3% CPU mid-race on my old laptop compared to 4-5% on the previous version. Memory usage is also down to about 180MB compared to 220MB before.

Mac and Linux builds of the game also exist, though are not yet available due to an outstanding texture issue that only seems to affect the Mac platform - this should be resolved once I get my hands on some actual Apple hardware, like one of the ten richest kings in Europe.

Getting there.

Friday, 9 August 2019

Last & Furious

In November 2017, Ivan Mogilko and Jim Reed created Last & Furious for a MAGS competition. Unusually for AGS, it was a top-down racer in the mould of SuperCars II. It went on to win a handful of annual AGS awards as it spoke to the versatility of that engine.

Fortunately, they also shared the source code on github. A previous attempt at porting it to XAGE hadn't gotten very far, as it relied heavily on functionality I hadn't yet implemented (DynamicSprites, new audio mechanism, scripted keyboard handling etc).

As work continues on [REDACTED], I periodically return to old ports as a palette-cleanser and also to see how far the conversion tools and engine have progressed. After a few weeks of late nights (with some additional pointers from Ivan), I'm happy to say the port is complete and now available on itch.io.

Download link: https://clarvalon.itch.io/lastandfurious (40MB, Win x64)

This is using the latest version of the XAGE engine, running on a standalone deployment of .NET Core 3. It is not using a CoreRT build as the .NET foundation have recently decided to instead focus on a different AOT approach for .NET 5 once it launches in 2020.

Performance seems decent - on my 6 year old laptop it averages at about 5% utilisation for both CPU and GPU while in the middle of a race. By comparison, the AGS version averages about 20% for CPU. This is likely because it is using a software renderer whereas XAGE is able to offload more work onto the GPU. I also optimised a handful of things along the way, so not exactly a fair comparison. Where AGS still trumps XAGE comprehensively is memory usage.

The conversion process was 95% automated. The C# generated should look very familiar to anyone comfortable with AGS Script:

There were a few manual tweaks to:

- Correct some AGS variable type inconsistencies (as with every port).

- Simplify some of the walkable areas, here used determine obstacles and how the car controls on various surfaces.

- Suppress pathfinding (as everything is handled manually).

- Change the scope of a handful of arrays to reduce the amount of garbage being generated (the game still generates a lot, but mainly Gen0, and not enough for it to affect performance).

- Prevent new DynamicSprites being created for every single rotation - instead let the GPU handle it.

- Force a custom texture to be stored locally (to speed up GetPixel calls).

I left in the debug hooks so pressing the usual console key (`) will open the ImGui debug console. It should otherwise look and feel identical to the original AGS version.

As I've been working primarily on something behind the scenes, it's nice to be able to show how general engine development is progressing!

As I've been working primarily on something behind the scenes, it's nice to be able to show how general engine development is progressing!

Sunday, 3 March 2019

Experimenting with CoreRT

I hope you like acronyms.

As work on porting [REDACTED] continues, I've been putting more thought into distribution. Now that XAGE uses .NET Core, we have the option to publish 'standalone' executables, which means there is no requirement to have a version of the .NET framework installed on the end user's machine. This is a good thing, though results in a version of .NET Core being bundled in with the final executable, which at the moment means lots of individual files and a much larger overall size.

There is a mechanism being developed to allow these individual files to be essentially be bundled together and extracted to a temporary location at runtime, though I'm not convinced that this is the best approach.

A more interesting prospect is leveraging CoreRT in order to compile everything ahead-of-time (AOT) into a native executable. This comes with some benefits:

At the cost of a few downsides:

The CoreRT project is still in early preview, but has made a lot of progress in the last few years. In the process of trying to get it work with XAGE, I came across a major stumbling block: CoreRT does not currently support XmlSerialization and Protobuf-net - both of which are serialization techniques used by XAGE. The reason for this is that CoreRT does not support Reflection.Emit, which generates Intermediate Language (IL) which is JITed into native code.

There are some changes on the way that should make both viable with CoreRT, but in the meantime I wanted to explore some different serialization techniques, which is when I discovered Biser. This little-known library allows you to generate serialization C# classes AOT that you can include in your final executables or libraries, meaning no run-time reflection is required (not dissimilar to something I'd first tried back in 2010). I was able to rewrite this and include it in the XAGE workflow such that it could be used as the single serialization method within the engine runtime:

And voilà, we have our minimum viable game runtime - here for Windows x64:

Where the executable is under 24MB and there are only 11 files in total:

I like this a lot, as we get the bleeding edge functionality & performance from .NET Core while also producing neat and tidy native distributables.

I'm not sure whether I'll stick with my fork of Biser (unimaginatively named Xiser) or return to Protobuf-net once it matures further and is able to support CoreRT. I have a lot more confidence in Marc Gravell's ability to maintain a robust & feature rich serializer than my own. But it's good to have options.

As work on porting [REDACTED] continues, I've been putting more thought into distribution. Now that XAGE uses .NET Core, we have the option to publish 'standalone' executables, which means there is no requirement to have a version of the .NET framework installed on the end user's machine. This is a good thing, though results in a version of .NET Core being bundled in with the final executable, which at the moment means lots of individual files and a much larger overall size.

There is a mechanism being developed to allow these individual files to be essentially be bundled together and extracted to a temporary location at runtime, though I'm not convinced that this is the best approach.

A more interesting prospect is leveraging CoreRT in order to compile everything ahead-of-time (AOT) into a native executable. This comes with some benefits:

- The final standalone executable is much smaller and completely self-contained.

- The startup time is much quicker as no just-in-time (JIT) compilation is required.

- General performance is better.

- Decompilation of the code is much harder with native executables compared to .NET.

At the cost of a few downsides:

- The process of the AOT compilation & linking to remove unused code means that you need to provide some details on items not to remove in the form of an XML file.

- One of FNA's selling points is that you can package your game with MonoKickstart in such a way that it will work for x86 and x64 Windows, Mac and Linux. Using CoreRT will mean that separate packages need to be prepared per platform.

The CoreRT project is still in early preview, but has made a lot of progress in the last few years. In the process of trying to get it work with XAGE, I came across a major stumbling block: CoreRT does not currently support XmlSerialization and Protobuf-net - both of which are serialization techniques used by XAGE. The reason for this is that CoreRT does not support Reflection.Emit, which generates Intermediate Language (IL) which is JITed into native code.

There are some changes on the way that should make both viable with CoreRT, but in the meantime I wanted to explore some different serialization techniques, which is when I discovered Biser. This little-known library allows you to generate serialization C# classes AOT that you can include in your final executables or libraries, meaning no run-time reflection is required (not dissimilar to something I'd first tried back in 2010). I was able to rewrite this and include it in the XAGE workflow such that it could be used as the single serialization method within the engine runtime:

And voilà, we have our minimum viable game runtime - here for Windows x64:

Where the executable is under 24MB and there are only 11 files in total:

- Four content files specifically for the XAGE game (game.zip, graphics.zip, audio.zip and voice.zip - the latter two of which are optional)

- Six native .dlls in the x64 directory - five required for FNA (FnaLibs) and one for Dear ImGui, which you probably wouldn't need as part of the Release build anyway.

- Strictly speaking I should also include FNA.dll.config, but it seems to work fine without.

I like this a lot, as we get the bleeding edge functionality & performance from .NET Core while also producing neat and tidy native distributables.

I'm not sure whether I'll stick with my fork of Biser (unimaginatively named Xiser) or return to Protobuf-net once it matures further and is able to support CoreRT. I have a lot more confidence in Marc Gravell's ability to maintain a robust & feature rich serializer than my own. But it's good to have options.

Tuesday, 1 January 2019

The state of things

Last march I committed to releasing XAGE publicly in 2018. This hasn't happened, but for a good reason.

For most of 2018 I've been working on a port of an upcoming commercial game, details of which are under NDA. The game itself represents a scale & complexity I've not worked with previously, and has helped focus attention on the areas that most needed work. At a high level:

There have been 745 commits to the XAGE source code repository in 2018. Counting commits is not the best metric, but it is a metric, and hopefully one that gives some indication that this project is very much a going concern.

Seeing the port of [REDACTED] progress from thousands of compile errors to a close facsimile of the AGS version has been very rewarding. It's not quite there yet - there is still plenty to do - but there have been times recently when debugging where I've forgotten whether I'm playing the AGS or XAGE version of the game. If the same rate of change can be maintained then with luck you'll be able to play [REDACTED] on Xbox One and other fancy platforms sometime in 2019.

For most of 2018 I've been working on a port of an upcoming commercial game, details of which are under NDA. The game itself represents a scale & complexity I've not worked with previously, and has helped focus attention on the areas that most needed work. At a high level:

- Several months were spent improving the AGS code parsing so that the converter could, in this case, automatically produce 36,000 lines of equivalent C#.

- Time was spent further optimising the Editor and build tools to handle the large volume of game items and assets, in such a way that re-ports can still be iteratively performed quickly.

- Font handling was rewritten to convert .ttf, .sci and .wfn formats to XNA-style spritefonts.

- Support for 'new-style' AudioClips & AudioChannels was introduced. DynamicSprites and DrawingSurfaces were also partially implemented.

- AGS scripting coverage jumped from 39% to 64% for properties and 50% to 62% for methods.

- Engine script-threading was re-written to more closely align it with AGS (i.e. Global & Room threads) and with some events being queued rather than run immediately.

- The AGS Exporter plugin now optionally uses Potrace (for vectorising walkable areas) and ffmpeg (for converting all audio to .ogg).

- The runtime now uses the latest version of FNA with FAudio handling the .ogg files.

- A runtime debug console was added using Dear ImGui & ImGui.Net, with a custom inspector and logger added to help with debugging.

There have been 745 commits to the XAGE source code repository in 2018. Counting commits is not the best metric, but it is a metric, and hopefully one that gives some indication that this project is very much a going concern.

Seeing the port of [REDACTED] progress from thousands of compile errors to a close facsimile of the AGS version has been very rewarding. It's not quite there yet - there is still plenty to do - but there have been times recently when debugging where I've forgotten whether I'm playing the AGS or XAGE version of the game. If the same rate of change can be maintained then with luck you'll be able to play [REDACTED] on Xbox One and other fancy platforms sometime in 2019.

Wednesday, 14 March 2018

AGS Script to C#

I've never been out on New Year's Eve. It always seemed noisy and expensive, and I've never been around people who were inclined to celebrate, so it stands to reason that I was working on XAGE on the evening of December 31st, 2017.

I'd posted some progress pics and got chatting to Scavenger, who kindly sent me the source code to his AGS game Terror of the Vampire. After poking around for a few hours I was able to convert the bulk of the game to XAGE, albeit with a worryingly large 10K+ of C# scripting errors.

At high volume the number becomes somewhat meaningless - a missing bracket can create hundreds of syntax errors in a single class - but it was clear this was a complex game that came with a lot of challenges:

By looking at the error patterns in Visual Studio, I was able to start whittling the error count down by improving the parsing, handling new data structures, implementing API placeholders and some workarounds for various AGS quirks and oddities (especially around scope). Two and a half months later and we're down to 81 errors following a fresh conversion.

The law of diminishing returns dictates that trying to automatically resolve these would involve a big time investment that is better spent elsewhere, given they are generally simple to solve by hand, and can often be fixed beforehand in the AGS source. They mostly revolve around C# being somewhat stricter than AGS code:

These are all simple things to fix manually, meaning we are now able to fully compile the C# solution and get in-game:

As can be seen from the screenshots, there is a lot of engine functionality that has yet to be implemented or isn't quite right, but this is where the real work begins. I will most likely start with DynamicSprite and DrawingSurface as these are all throwing null exceptions currently and are used throughout this game. This is where I finally start to flesh out the Engine API and turn some of those table cells green.

A big caveat is that AGS Engine plugins still remain unsupported - for the time being I added a few placeholder classes to act as a dummy implementation to allow the code to compile. It may be that we can autogenerate C# bindings to the original C++ plugin .dll, but the simpler option may be to simply re-implement each required plugin in C# and keep everything in managed code.

Other items

I'd posted some progress pics and got chatting to Scavenger, who kindly sent me the source code to his AGS game Terror of the Vampire. After poking around for a few hours I was able to convert the bulk of the game to XAGE, albeit with a worryingly large 10K+ of C# scripting errors.

At high volume the number becomes somewhat meaningless - a missing bracket can create hundreds of syntax errors in a single class - but it was clear this was a complex game that came with a lot of challenges:

- Massive AGS Modules like Tween were used which were not being parsed well.

- AGS Engine plugins were used and unsupported.

- AGS-style structs were used throughout, which were not being parsed and converted into equivalent C# classes.

- There were gaps in the scripting API, mainly due to newer AGS functionality as part of version 3.2 - things like AudioClip and AudioChannel.

By looking at the error patterns in Visual Studio, I was able to start whittling the error count down by improving the parsing, handling new data structures, implementing API placeholders and some workarounds for various AGS quirks and oddities (especially around scope). Two and a half months later and we're down to 81 errors following a fresh conversion.

The law of diminishing returns dictates that trying to automatically resolve these would involve a big time investment that is better spent elsewhere, given they are generally simple to solve by hand, and can often be fixed beforehand in the AGS source. They mostly revolve around C# being somewhat stricter than AGS code:

- Casting. C# doesn't like to implicitly cast certain types, like a bool or char into an integer. AGS is rather lax about typing. The solution is to add an explicit cast.

- Function integrity. AGS allows you to define a function with a return type and not actually return anything. C# does not ("not all code paths return a value"). Solution is to fix the return values.

- Method variable scope. AGS allows you to define variables within inner blocks that share the same name as a variable in the outer block. C# does not. Solution is to fix the scope or rename the variables.

These are all simple things to fix manually, meaning we are now able to fully compile the C# solution and get in-game:

As can be seen from the screenshots, there is a lot of engine functionality that has yet to be implemented or isn't quite right, but this is where the real work begins. I will most likely start with DynamicSprite and DrawingSurface as these are all throwing null exceptions currently and are used throughout this game. This is where I finally start to flesh out the Engine API and turn some of those table cells green.

A big caveat is that AGS Engine plugins still remain unsupported - for the time being I added a few placeholder classes to act as a dummy implementation to allow the code to compile. It may be that we can autogenerate C# bindings to the original C++ plugin .dll, but the simpler option may be to simply re-implement each required plugin in C# and keep everything in managed code.

Other items

- I've foolishly committed to releasing XAGE in some form or other this calendar year.

- There has been some promising experimentation around embedding VS Code directly into XAGE Editor for a more seamless (if diluted) user experience.

- PUBG is still causing me an enormous amount of pain.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)